Lean is all the rage these days, thanks to ‘The Lean Startup’ by Eric Ries. If you run a PR agency and you have worked with a startup or a big manufacturer, chances are that you’ve heard the gospel of ‘lean’.

In fact, you may well have already run into some of the approach’s more popular manifestations. Task management app Trello, for example, is based on the principle of ‘kanban’, which was developed as part of lean manufacturing.

Lean is a manufacturing process that was originally created by Toyota in the sixties and seventies. It is based on three simple principles:

- Minimise waste

- “Pull” items through the process instead of “pushing”, i.e. let demand drive the pace instead of letting production set the pace

- Continuously look to improve the process

In manufacturing, lean has been a huge success – as evidenced by the meteoric rise of Toyota. But in services, the introduction of lean methods was a lot less successful.

In fact, you might have encountered lean services – and hated it. You know those computerised phone menus where you have to “Press 1 for…”, “Press 2 for…”? That’s an instance of lean applied (badly) in a service environment.

In their paper “Rethinking Lean Services”, researchers Seddon, O’Donovan and Zokaei argue that the reason lean services do not keep their promise is because they fail to see that services are completely different from manufacturing.

1. Learn the difference between “value demands” and “failure demands”

The key to unlocking the value of the lean philosophy is to take a step back and realise the differences between services and manufacturing, says Seddon.

In services, it is not about creating the most efficient processes to force customers through. Instead, it is about understanding what the customer asks.

“we need to understand more about customer demand – what customers want”

And here’s a shocking bit of information:

“From the customer’s point of view, you learn that much of the demand is waste and, worse, it creates further wasteful activity.”

Surely that’s a bit harsh, you’ll say? Well, no. For a customer, two outcomes are possible when he engages with a service process. Either the customer achieves what he wanted, or he doesn’t. In the first case, the process created value, in the second, your company created failure. The authors coin the terms “value demand” and “failure demand” to distinguish between the two.

Typically, a failure demand is caused by not understanding the customer’s request correctly.

More broadly, a failure demand is every demand by a customer or a colleague that does not create value for the customer. This includes questions by the client to correct mistakes, typos and such things, but also requests like “You haven’t forgotten about X, have you?”, “Where are you on Y?”

These requests take up valuable time, but they don’t add to the success of your work. Failure demands are incredibly harmful to your company (and your relationship with your customer). You and the customer are both spending time that does not result in added value.

Worse, your customer will have to “try again” by asking you to redo your work. In other words, he is paying twice for what you should have gotten right in the first place.

2. Root out “failure demands” – fanatically

Seeing your work in terms of value demands and failure demands requires you to look beyond billable time. Because the trap about failure demands is that they can appear to be productive. You might be able to invoice your customer for doing two or three versions of a press release, but you are surely not adding more value.

You are merely providing the value that your customer was asking you to produce the first time. You are wasting the customer’s budget, and you’re wasting more of it than you realise:

In financial services, failure demand can account for anything from 20 to 60 per cent of all customer demand.

A real life example: my heating system broke down last week. I told the customer agent on the phone what the likely cause of the breakdown was. My guess turned out to be right, but on his first visit the technician didn’t bring the piece. Value added on first visit: zero.

On the second visit, the technician managed to repair the piece, but created a leak when repairing the system. The third time, they made the leak worse. Only on the fourth attempt did they finally manage to repair my heating system. How this firms makes a profit is beyond me.

As the owner of an agency or a service firm, it’s very useful to ask yourself: are you like this firm? To some degree, you probably are – and it means you’re burning money and hurting your firm.

It’s quite common in agency settings to say that “customer expectations” were too high. But research shows that B2B customers are actually quite well informed about the quantity and quality of work they can expect your firm to deliver.

This means that your customers will know it when your firm is not delivering the value they can expect, and they will complain. They will pressure you to lower your hourly rates or overservice, and in general, they will tell their colleagues and peers that they were not happy with your services.

Both overservicing and negative word of mouth will negatively impact your business in the long run. And as we will see, they are avoidable if you manage to root out “failure demands”.

3. Don’t standardize your services. Train your people instead.

If failure demands are such a problem, why do these computerised phone menus exist? Because they are applying the ideas of lean on the wrong kind of activity.

Phone menus try to standardize services. They try to force the customer through a process defined by the service provider. It’s not very customer friendly, and actually increases failure demands:

In service organisations work typically has been standardised and industrialised (…).The consequences are more handovers; more handovers means more waste, and an increasing likelihood of failure demand (further waste).

Standardized phone menus try to shape the customer’s demand into a “supplier shaped” solution: you are trying to tell the customer that you know what he will ask, and that you know how you will solve it – before you have even listened to his demand. This is the wrong approach.

As Seddon writes: ‘customers make customer shaped demands’. Your job as a service provider is to answer the customer’s specifically shaped demand with a service that matches the demand – you should not try to tell the customer that he actually wants something else instead, because that will only make them angry (just like phone bank software makes you angry).

In any service firm, there is the idea that we should created “packages” and “products” – the idea being that if we can force the customer into certain templates, we will prosper more. Seddon’s article suggests that the reverse is actually true: you will thrive as a PR agency if you manage to handle very diverse requests from clients, and deliver them all at the highest quality. The answer here is not to create “templates”, “products” or “menus” that your people can execute without thinking too much. The answer is to train your people to understand these requests, allow them to use their brains and deliver projects in a highly customised way that will delight your customers.

4. Aim for “single piece flow”

Lean also gives a few interesting ways to reduce failure demands. One of them is simply: avoid handovers and try to deliver work in a “single piece flow”. Single piece flow means that the work can be completed wihout interruption, or without being sent back to colleagues or the customer for clarification.

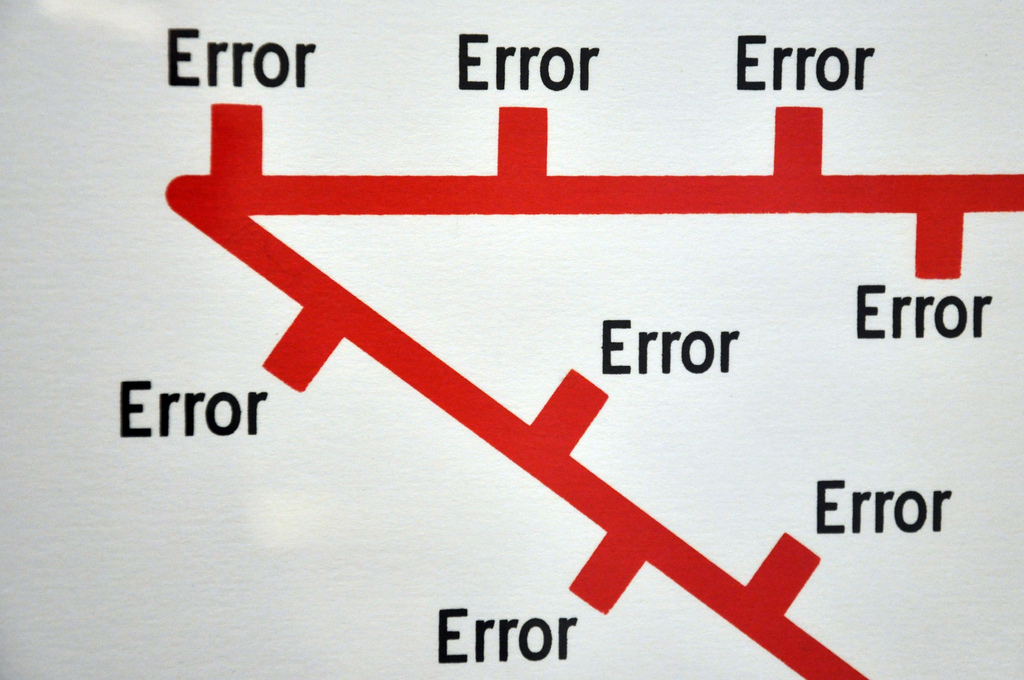

This means that you should train everyone at your service company to be able to handle the most frequent “value demands” from start to finish. Seddon calls these high frequency value demands – the 20 percent of activities that make up for 80 percent of your revenue. In the case of a PR agency, these are typically things like: sending out a press release, doing follow up by phone to journalists, creating a blogger care package, doing an influencer mapping, and all similar bread and butter activities. You don’t want this work to be “pingponged” around the office, because every handover increases the likelyhood of errors.

If a handover has to happen, care should be taken to manage a a “clean” handover, meaning that the person who receives the assignment can finish it without further questions to the customer or the person who handed it over to them.

5. Create a “pull” system to solve difficult demands

Of course, there’s the other 80 % value demands that are so niche that you can’t train your entire staff to deal with them. Here, you should make use of the “pull” principle of lean manufacturing.

When a staff member gets a demand he cannot solve, you should make sure that he can “pull in” expertise as needed to solve the demand (or hand it over – cleanly).

6. Involve the frontline in improving the processes and training

A last important insight of lean is this: it is the people who actually do the work who have the best ideas to improve it. Since they are closest to the customer, they are best placed to understand what the customer wants – and how your firm is or isn’t delivering on it. Don’t try to force their work into processes that you design behind your desk. Instead, involve them in improvements to handle value demands, and the training that their colleagues receive for these value demands.

The end result should be more value added for your customers, which leads to more satisfied customers, less overservicing and the ability to consistently charge higher rates than your competitors.

Is focusing on waste enough to become more profitable? Probably. There is always more waste to tackle, and it is surprising how much waste a typical company generates while working.

The typical car manufacturer, for instance, is only creating value for the end customer in five percent (5 %) of its activities. The rest is “waste” in the sense that it doesn’t bring immediate value to the customer. At Toyota, the percentage of the company’s activities adding direct value for the customer is estimated at twenty percent (20 %). While this is a difference of 15 percent points, Toyota is actually performing 300 percent better than its competitors. It makes for quite the difference in the bottom line.

Imagine how much more profitable your firm can become if you can direct all its energy on creating value instead of waste. As Seddon says:

“focusing on the costs lowers quality and increases costs. Focusing on quality decreases costs and improves profitability.”

Do you apply any of these “lean” principles at your PR agency? I’m curious to hear – let me know in the comments.

Image: Nick Webb, Flickr Creative Commons